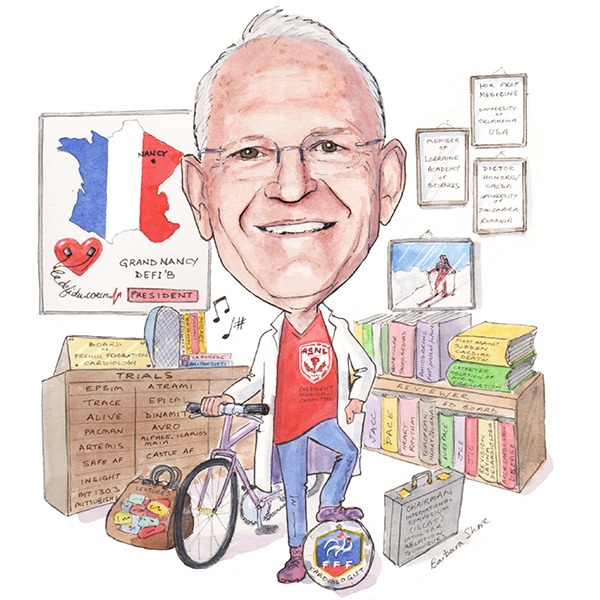

Etienne Aliot (Nancy, France) has always been fascinated by the work of surgeons. This fascination set him on his path through medical school. He has since been at the forefront of many electrophysiological research initiatives, including influential consensus documents and guidelines on a range of conditions. He has acted as chairman of the Working Group on Cardiac Arrhythmias of the French Society of Cardiology and of the European Society of Cardiology (precursor of EHRA). In the fight against sudden cardiac death, he has also been involved in developing practical screening and emergency response programmes through his work for the French Federation of Football and Grand Nancy Defi’b Association. Aliot spoke to Cardiac Rhythm News about the lessons he has learned from his varied career to date and what he thinks can be done to further improve electrophysiology treatment in the future.

Etienne Aliot (Nancy, France) has always been fascinated by the work of surgeons. This fascination set him on his path through medical school. He has since been at the forefront of many electrophysiological research initiatives, including influential consensus documents and guidelines on a range of conditions. He has acted as chairman of the Working Group on Cardiac Arrhythmias of the French Society of Cardiology and of the European Society of Cardiology (precursor of EHRA). In the fight against sudden cardiac death, he has also been involved in developing practical screening and emergency response programmes through his work for the French Federation of Football and Grand Nancy Defi’b Association. Aliot spoke to Cardiac Rhythm News about the lessons he has learned from his varied career to date and what he thinks can be done to further improve electrophysiology treatment in the future.

Why did you decide to go into medicine and why, in particular, did you choose to specialise in electrophysiology?

Ever since I was a child I have been fascinated by the work of surgeons. After graduating from medical school, I became aware of many other interesting opportunities but my decision to specialise in cardiology came from one encounter with a cardiologist during my first year of residency. The cardiologist, who had just come back from the “Sodi Pallares Institute” in Mexico—one of the leading centres in electrocardiography at that time—shared with me his passion for ECG and vectography interpretation, and his teaching was so good that I decided to follow his path.

I did specialise in cardiology and of course turned my interest towards electrophysiology (EP). At the end of my fellowship, I became an assistant professor when echocardiography and invasive cardiology were just emerging and EP was in its infancy. At the end of my role as an assistant professor I had the opportunity to work in clinical research at the Oklahoma University Health Center.

The evolution of EP from diagnosis to therapy in the 80s led me to perform invasive procedures, so I could act a little bit like a surgeon.

Who were your career mentors and what have you learned from them?

I have had the fortune to learn cardiology and EP with great mentors. One of them is Jean-Marie Gilgenkrantz and the entire team at the Oklahoma University Health Center, led by Ralph Lazzara with Ben Scherlag, Dwight Reynolds and Sonny Jackmann.

Jean-Marie Gillgenkrantz guided my first steps in cardiology and placed his trust in me from the very beginning. I was his fellow, his assistant and an assistant professor alongside him. The year I spent in Oklahoma was a major influence on my career. I split my time between the basic lab and clinical EP as my path crossed that of Sonny Jackmann who had just arrived in the department. I remember so well the mornings in the lab with Ralph Lazzara and Ben Scherlag—“Mr one day, one idea”. In this period, catheter ablation—fulguration—was performed only to ablate the atrioventricular (AV) node, and we used to spend hours in the EP lab with Sonny recording the accessory pathways with the orthogonal catheters. These are fascinating memories.

All these masters were not only some of the best scientists I have closely worked with, but wonderful human beings. They developed original concepts and technologies, never forgetting the importance of the relationship with our patients. Thanks to Ralph Lazzara and then Dwight Reynolds later on, I was introduced to NASPE and then HRS of which I have been part of the Board of Trustees for several years.

During your career, what has been the biggest development in electrophysiology?

Evolution in medicine is rapid and in constant change. We have to keep in mind that when I started to be involved in EP, we used to perform studies with the sole purpose of giving a diagnosis or finding mechanisms of arrhythmias. We were regarded as friendly “chess players”, brilliant at discovering concealed information from the recordings, but challenged in the therapeutic aspect, limited to the few same and poorly effective drugs.

The beginning of the 80s was the biggest turning point. This period saw, on one hand, the rapid development of catheter ablation through direct current, then radiofrequency, making us rapidly able to successively tackle almost all arrhythmias (except atrial fibrillation). On the other hand, we saw the development of implantable defibrillation. These two technical developments contributed to give its credentials to EP.

What has been the biggest disappointment—ie. something you thought would be practice-changing but was not?

What has been the biggest disappointment—ie. something you thought would be practice-changing but was not?

It is the nature of the life of clinicians and researchers that we face failures. Among many, I have been personally involved in two “adventures” of drug development—from phase 1 with the first healthy volunteers in my department to phase 3—and I was very confident regarding the potential of these new antiarrhythmic drugs. Unfortunately, it transpired that for different reasons, their development had been stopped at the very last step before marketing, sending several years of work and millions of euros up in smoke. The dream of a new amiodarone without side effects is still far away.

Of the tasks you have been involved in, what do think has had the biggest impact?

I am proud of what I have tried to do since the very beginning in all the aspects of the fight against sudden cardiac death, from the acceptance in our country of the first implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), which was a matter of debate as to the efforts developed to obtain the authorisation of spreading automated external defibrillators (AEDs) in the public domain.

I am also proud and honoured to have been part of many consensus documents and guidelines (on atrial tachycardias, ventricular arrhythmias, ICD indications, atrial fibrillation management, etc), especially one of the most recent on ventricular tachycardia catheter ablation, which I have been honoured to lead in the name of EHRA/HRS with William Stevenson.

What are the research priorities in the field of catheter ablation?

Atrial fibrillation ablation seems mature but it is still young (less than 20 years) and has many challenges to face in order to be proposed more broadly to better selected patients, including becoming still more effective, simpler, safer and less expensive. The development of new technological tools, re-birth of robotics and the growing role of imaging will certainly help in this matter.

Today many eyes turn to the ventricle and ablation of ventricular arrhythmias is performed successfully in many centres.

More generally in the EP field, I am fascinated by the percutaneous implant of miniature active electronics for diagnostic or therapeutic applications and in parallel, the development of telemedicine and connected care/e-Health through devices such as smartphones, which puts the patient at the centre of the scene.

What has been your most memorable case?

Like many of us, I have many stories that are too long to tell! One seems very simple and of no real interest, but I remember my first AV node ablation, a few days after the first procedures in the USA: There was no ethical committee, instead there was a do-it-yourself system with a lead of an external defibrillator connected to a basic EP catheter and an old patient on a life support machine with irrepressible fast atrial tachycardias. We achieved success, stopped using the machine the day after, and the patient lived for seven years post-procedure. If instead the patient had died, it would have been a long time before I would have been ready for another similar procedure.

You are chairing the International Symposium on Catheter Ablation Techniques (ISCAT; 12–14 October, Paris, France). What do you think the highlights of this meeting will be?

One entire session will be devoted to our actual knowledge of the atrial fibrillation mechanisms involving a debate on the role and importance of rotors in atrial fibrillation and the role of fat and fibrosis.

Of course technology is rapidly evolving with innovations such as non-invasive mapping which will be updated by ISCAT co-chair, Michel Haissaguerre, not only at the atrium level but at the ventricular level as well.

Many sessions will be dedicated to persistent atrial fibrillation. Catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias takes up more and more room in the symposium as it does in our daily practice. New mapping and ablation techniques including image integration will be tackled, as well as the place of early ablation of ventricular tachycardia, which is presently an important clinical issue.

According to the programme, the meeting will have “highly practical sessions”. What will these sessions consist of and why is it important to have such sessions?

First of all, we did not choose to propose “live sessions” as they often may be difficult to practically manage during a meeting and to fit in the programme. We preferred to select videos of cases illustrating the difficulties, tips and tricks in real-world experience.

Second, we asked several experts to deal with challenging cases in index and redo procedures of persistent atrial fibrillation ablation and to propose their approaches.

Third, as usual, the RETAC, (a small group of European electrophysiologists) will propose workshops on interpretations of ECGs, EGMs, and 3D mapping.

Actually all these practical aspects are strongly encouraged and enjoyed by our youngest colleagues who need to share their experience with the experts. This then more closely reflects the issues that they may face every day in their practice.

You are a cardiologist for the French Federation of Football (FFF). What does the role involve?

Five years ago, I was asked to join the Medical Committee of the FFF as a cardiologist. We have launched several campaigns to fight against sudden cardiac death. First, we organised and financed training in first aid intervention with the campaign “One player, one referee, one manager and the coach for a team” in every district of the FFF. Since then, 40,000 people have been trained. This action seems of major importance when we know that the links in the chain of survival are fully effective when performed altogether.

Second, we have created a committee of experts in sport cardiology in order to help the medical staff of the professional teams who are put under pressure by players, the club presidents, and coaches, when facing difficult cases, such as those in the grey zone of the guidelines (such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathies or channelopathies, etc).

What is your view of mandatory ECG screening in athletes?

This applies not only for top athletes but for children and adolescents in their leisure time as well. There is a long-standing controversy about whether ECG should also be mandatory for all athletes. ECG is usually rejected in the USA but included in most European countries.

In addition, some large sports organisations also require ECG of athletes. The resting ECG can detect potential life-threatening diseases such as cardiomyopathies or ion-channel diseases, thus avoiding sudden cardiac events or even death. Arguments against this include organisational problems, as sports physicians are not present nationwide. Other arguments are the lack of large prospective studies demonstrating reduced mortality by ECG and the low sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of ECG. In summary, the cost-effectiveness of such screening programmes is challenged.

However, current studies and new stringent and reliable criteria for ECG interpretation (eg. the Seattle criteria) have increased its validity. This is also supported by new, athlete-related ECG interpretation software in ECG devices, which are more reliable than visual analysis. This also may reduce legal problems, while the fact that psychological problems are of low importance as has been shown recently. Therefore, ECG recording in all athletes is strongly recommended in Europe. ECG is superior to history and clinical exam in detecting hidden and congenital diseases.

However, special education in sports cardiology is advised, and courses and training in ECG interpretation in athletes—as well as special ECG devices—are mandatory for correct ECG interpretation. I am personally in the pro-ECG camp.

As the president of the Grand Nancy Defi’b Association—an organisation dedicated to improving the prognosis of cardiac arrests by incorporating citizen volunteers in Nancy, France; could you tell us the most significant goal achieved with this association?

This association is now almost ten years old. The initial idea was to improve the chain of survival in Nancy in adding one more link to it, ie. a volunteer-based close to location of the accident. We realised that in many places, the witness of sudden cardiac death calls for help, starts heart massage and starts resuscitation manoeuvers, but does not look for or find an AED.

When the operator receives a call reporting a sudden cardiac death, and sends the emergency services, he or she then calls the volunteer, a citizen on call in the area (localised on the map as not further away than 400m). The volunteer has an ICD at his or her disposal and may precede the emergency services by several minutes, again in time which may save the patient.

The percentage of people in the city saved thanks to this organisation has more than doubled.

If you have not been a doctor what would you have been?

Like most of us, I regret that we cannot have several lives in order to experience many fascinating jobs. Among those, I probably would have liked to be an archaeologist as I learned ancient languages when I was in school, or—although it is only a dream—an orchestra conductor!

Outside medicine, what are your hobbies and interests?

Sport. Not only am I involved in the football world but I also practice skiing avidly in winter and biking all through the year. I also strongly believe that “a world without music would be an error” and I am fond of classical music, without of course forgetting the importance of my entire family.

Fact File

Present appointments

Head of the Cardio Medico Surgical Center of the University Hospital in Nancy, France

Member of the Board of the French Federation of Cardiology

Chairman of the International Symposium on Catheter Ablation Techniques

Cardiologist of the French Football Federation

President of the Grand Nancy Defi’b Association

Past appointments

Chairman of the Working Group on Arrhythmias of the French Society of Cardiology

Chairman of the Working Group on Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology

Member of the Board of Trustees of NASPE then HRS

Education

1976 Doctor in Medicine, University of Nancy, France

1976 Board certification in Cardiology

1976 Assistant professor in Cardiology, University of Nancy, France

1983‒1984 Visiting professor in Cardiology, Oklahoma City, USA

1985 Full professor in Cardiology, University of Nancy, France

Distinctions

Honorary professor of Medicine, University of Oklahoma, USA

Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Timisoara, Romania

Member of the Lorraine Academy of Sciences

Books

Ventricular tachycardias edited by E Aliot and R Lazzarra, 1987

Amiodarone: past, present, future edited by E Aliot and R Lazzarra, 1990

Fight against sudden cardiac death edited by E Aliot, E Prystowsky and J Clementy, 2000

Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation edited by E Aliot, M Haissaguerre and S Jackman, 2008

Editorial board member

Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology

Journal of Interventional Electrophysiology

Europace

Revista Latina de Cardiologia

Arch Cardivasc Diseases