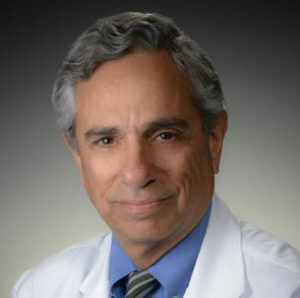

Mark E Josephson, a pioneer of clinical cardiac electrophysiology (EP), passed away at the age of 73 on 11 January 2017 after a courageous battle with cancer. With his passing, the EP community lost a great physician whose achievements will be remembered for years to come. Andrew L Wit (Emeritus Professor of Pharmacology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, USA), a close professional colleague and friend of Josephson for over 40 years, writes this tribute for Cardiac Rhythm News.

Mark E Josephson’s death is an extraordinary loss to his family, friends, colleagues and to medicine and cardiology. His life was inextricably intertwined with the development of clinical cardiac EP. Josephson was one of the pioneers of this relatively new medical discipline which was born in the 1960s. A recently published book details his legacy and aptly identifies the “Josephson School” of electrophysiologists trained by him, who will carry out his legacy.1

When Josephson began his electrophysiology training in the laboratory of Anthony N Damato at the US Public Health Service Hospital in Staten Island, USA, in 1971, clinical EP was in its infancy. Brilliant minds over five decades following the invention of the electrocardiogram (ECG) in 1903, using deductive reasoning, had established classifications of arrhythmias according to sites of origin, and hypothesised mechanisms.2 However, clinical EP was not born until the 1960s when invention of the electrode catheter enabled the heart to be electrically stimulated directly and electrical activity to be recorded from localised regions without thoracotomy, in Amsterdam and in Paris independently. In Amsterdam, Dirk Durrer, Hein J Wellens and Reinier Schuilenburg showed that programmed premature stimuli using a specially designed stimulator, applied to the atria or ventricles initiated tachycardia in patients with accessory atrioventricular (AV) pathways.3 This was the origin of programmed electrical stimulation (PES) to induce and terminate tachycardias that were interpreted to be caused by reentrant excitation. Subsequently Wellens and his colleagues used PES and intracardiac recordings to demonstrate that other supraventricular tachycardias as well as ventricular tachycardias could be induced and terminated by stimulation and were also likely caused by reentry..3,4

The Damato group then began using PES of the atria to define conduction and refractory properties of the components of the AV junction in normal and diseased hearts. The Damato lab was one of the earliest laboratories in the USA that had a major involvement in the development and growth of clinical EP owing to the pioneering development of the catheter technique for recording electrical activity from the His bundle by Benjamin J Scherlag in that laboratory.5 Josephson’s initial research with this group described the clinical EP of antiarrhythmic drugs, properties of the AV conduction system, and mechanisms of supraventricular tachycardia.1,6 Perhaps more importantly, this is where he began to formulate his ideas about mechanisms and treatment of ventricular tachycardia (VT).

After leaving this laboratory, Josephson went to the University of Pennsylvania in 1973 to join a fledgling cardiac EP group and within a few years, was head of that group while still a cardiology fellow. It was at Penn in the mid to late 1970s that he began to publish his series of ground-breaking studies that has had a lasting influence on clinical EP to the present day. Josephson and colleagues used systematic multi-site programmed stimulation to initiate and terminate sustained VT resulting from myocardial infarction7 and developed the technique of endocardial catheter mapping of VT.8 This approach led to recognition of the subendocardial origin of the majority of these arrhythmias adjacent to aneurysms.8 What followed was the innovative surgical technique of subendocardial resection where a subendocardial layer of tissue was stripped off from around an aneurysm (along with resection of the aneurysm).9 Continuing these investigations, the Josephson group described the properties of the electrophysiological substrate for VT. Mapping during sinus rhythm, they showed abnormal electrograms that provided markers for locating the reentrant circuits.10 Subsequent investigations defined the properties of the circuits including their size and shape, the cause of slow conduction, the nature of the excitable gap and localisation of the pathways using the 12 lead ECG.1

This extraordinary output of new and exciting information on the electrophysiology of VT in the late 1970s and 1980s were eventually translated into innovative therapeutic methodologies, which are now widely used tools of clinical EP. These methodologies include PES to induce and terminate VT, catheter mapping during sinus rhythm and VT to locate the sites of reentrant circuits, entrainment techniques to locate the critical isthmus of the circuits and catheter radiofrequency ablation at critical sites to prevent VT, replicating the effects of the original subendocardial resection technique.

Josephson continued his studies on VT after he moved to Beth Israel Hospital, Boston, USA, in 1992, where he eventually became chief of cardiology. All in all, he eventually co-authored over 50 publications on this subject. In addition, he contributed to our current understanding of AV nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrial flutter and fibrillation and ventricular fibrillation and defibrillation. He helped design and participated in many major clinical trials that have altered and improved clinical care of patients with arrhythmias (references to all his studies can be found in reference 1).

Throughout his career, Josephson was devoted to teaching and training the next generation of cardiac electrophysiologists. His nurturing of his fellows who became life-long friends, produced the second generation of clinical electrophysiologists that have made many important contributions of their own to the growth of clinical EP. They now have their own students (third generation) entering the world of electrophysiology. These generations insure that the Josephson School of Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology and Mark Josephson’s legacy will be perpetuated.1

Josephson has also reached thousands of electrophysiologists through courses at both the beginning and advanced levels in the United States and Europe. These courses have been mostly taught with Wellens (Cardiovascular Research Institute, Maastricht, The Netherlands) who as mentioned above, was one of the founding fathers of clinical EP. Many of the courses were mechanism-based. The philosophy of this approach is centred on the belief that an understanding of mechanisms is the foundation of future development of clinical cardiac EP. The treatment of patients should not be based only on published algorithms for the type of arrhythmia under consideration but should also involve an understanding of the basic electrophysiology. Those students who master these basics will be the ones who will make innovative contributions and devise new therapies in the future. To this end he also wrote the “bible” of clinical electrophysiology, Josephson’s Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology, which is now in its fifth edition.11 It is one man’s approach to the practice of clinical EP based on his many years of experience. It is extraordinarily comprehensive. Another textbook focused more on basic electrophysiological mechanisms just went to press.12

I had a close personal and professional relationship with Mark Josephson throughout our careers. I have worked with him in the laboratory and the class room and have spent many hours with him at the dinner table over the past 40 years. He has been an important part of my life. I will miss him greatly.

References

- Wellens HJ, et al. The Josephson School. A legacy of important contributions to electrophysiology. Cardiotext 2016

- Scherf D and Schott A. Extrasystoles and Allied Arrhythmias. A William Heinemann Medical Book Publication 1973

- Wellens HJJ. Electrical stimulation of the heart in the study and treatment of tachyarrhythmias. Leiden: Stenfort Kroese 1971

- Wellens HJ et al. Electrical stimulation of the heart in patients with ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 1972;46:216‒226

- Scherlag BJ et al. Catheter technique for recording His bundle activity in man. Circulation 1969;39:13‒18

- Josephson ME et al. Effects of lidocaine on refractory periods in man. Am Heart J 1972;84:778‒776

- Josephson ME et al. Recurrent sustained ventricular tachycardia. 1. Mechanisms. Circulation 1978;57:431‒440

- Josephson ME et al. Recurrent sustained ventricular tachycardia. 2. Endocardial mapping. Circulation 1978;57:440‒7

- Josephson ME et al. Endocardial Excision: A new surgical technique for the treatment of recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 1979;60:1430‒1439

- Cassidy DM et al. Endocardial catheter mapping in patients in sinus rhythm: Relationship to underlying heart disease and ventricular arrhythmias. Circulation 1986;73:645‒652

- Josephson ME. Josephson’s clinical cardiac electrophysiology. Techniques and interpretations. Wolters Kluwer 2016

- Wit AL, Wellens HJ and Josephson ME. Electrophysiological foundations of cardiac arrhythmias. A bridge between basic mechanisms and clinical electrophysiology. Cardiotext (in Press)

Tributes for Mark E Josephson

Electrophysiologists such as David Callans, Eric Prystowsky, Jonathan Kalman and Peter Kowey and David Steinhaus and Julie Stephenson, both from Medtronic, pay tribute to Mark E Josephson.

David Callans, University of Pennsylvania, USA

The world of electrophysiology has lost a genius founding father, and I lost a great friend.

Mark Josephson died just before his 74th birthday. Oh, but how he lived!

His extensive achievements and intellectual triumphs aside, what made Mark really amazing to the people who knew him was his expansive and often challenging personality. He was dedicated to make both himself as well as everyone he cared for as successful as they could possibly be, as a scientist, physician but especially as a human being. Although it took me a long time to understand, he was not interested in his disciples being as good as he was (thankfully, as this would have been impossible!), but was passionately concerned that they simply strive to be the best version of themselves. Around Mark, there was no avoiding this destiny though—halfhearted efforts were always called out in an aggressive but supportive way.

One of my favourite memories characterising this attribute occurred during his last year at Penn. I was hanging out in his office when one of the cardiology fellows who was senior to me, and graduating that year walked in to sheepishly confess that he was “abandoning” an academic career and had taken a position in private practice. While he feared disappointing what he thought were Mark’s aspirations for him, Mark had actually been instrumental in getting him that position. He said: “I want you to be the best doctor that you can possibly be, that is what I want for you.”

My relationship with Mark started during my fellowship, way before I was even a little equipped to understand anything he was talking about. I would travel to his Gladwyne home for discussion about the nature of the ventricular tachycardia circuit (I so wish I had kept the diagrams he scribbled out on napkins during those talks) and the nature of life, both his and mine. I had not a chance to fully develop my sense of gratitude for his taking me on as a student, enthusiastic but slow as I was, but Mark was offering so much more, even from the start. He was offering incredibly loyal friendship, an opportunity to share in his life, not just in his work. I was and continue to be overwhelmed by this.

At his funeral, his daughter Rachel said that Mark made everyone around him feel like they were Mark’s best friend. He meant so much to so many.

He shared a birthdate with another genius, Mozart, who authored a quote that I feel personifies Mark:

“Neither a lofty degree of intelligence nor imagination nor both together go into the making of a genius. Love, love, love is the soul of genius.”

Despite a profound sense of loss, his love, his ideas and his passion live on in all his dedicated disciples.

Eric Prystowsky, St Vincent Hospital, Indianapolis, USA

It is an honour and privilege for me to pay tribute to Mark Josephson, a friend for many years and one of the pioneers of our field of clinical electrophysiology (EP). During the first decade or so of the new field of clinical EP, there were five key individuals who investigated and opened up the areas of research and clinical care for patients with arrhythmias: Hein Wellens and John Gallagher (my mentor) for Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, Ken Rosen for atrioventricular node reentry, Michel Mirowski for the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) and Mark Josephson for ventricular tachycardia (VT).

My training in clinical EP at Duke emphasised the EP laboratory and operating room diagnosis and treatment of supraventricular tachycardias, with little exposure to VT. As EP lab director at Indiana University my main focus became the study and treatment of ventricular tachycardia. I contacted Mark and asked if I could spend some time with him to learn how to map VT, which he graciously agreed to do. In fact, we spent almost the entire day together discussing his findings and observing him mapping the left ventricle. It was clear how much he loved to teach and I never forgot this act of kindness. Several years later I developed a course for fellows, taken from the model of Pick and Langendorf, on the interpretation of unknown intracardiac electrograms that Mark participated in for many years. The fellows “loved him” and he did an outstanding job teaching these unknown tracings with me and the other faculty.

Mark Josephson was a very bright light in the field of clinical EP, who will be remembered for his many contributions to the understanding and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias and his outstanding role as a teacher and mentor. I already miss him.

Jonathan Kalman, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia

I first met Mark in person at an electrophysiology (EP) teaching session during my junior faculty year at University of California San Francisco (UCSF) in 1996 when he was a v

isiting lecturer. On that day I was (anxiously) prepared for the probing questions that Mark was renowned for and even though I acquitted myself with a pass on a case of antidromic tachycardia I received a lesson in his systematic and deductive approach that has stayed with me throughout my career.

Of course, I had met Mark many times before that in the words of his monolithic textbook from which my passion for EP began. In addition, I came to realise that many of the electrophysiologic truisms that I learned from one of my direct mentors, Michael Lesh, indeed had originated with Mark, Mike’s teacher and mentor. In turn, I have had the opportunity to pass those “pearls” on to the next EP generation.

Mark never failed to emphasise that, even in the era of computerised mapping and anatomically-based ablation, the greatest and most rewarding challenges in arrhythmia diagnosis still lay in the deductive reasoning of classical EP. With the aid of critically timed stimuli interacting with reentrant circuits and some well positioned catheters even the most complex of arrhythmias could be accurately described. This is one of the messages that reverberates across Mark’s work and throughout his teaching.

Over the years since we first met, I have greatly valued Mark’s friendship and the wisdom and intellectual integrity he has been prepared to share. His genuine interest in my career and knowledge of my work on each occasion that we met has been humbling. I am fortunate indeed to be able to count Mark Josephson among my teachers and mentors. I am all the more enriched for having counted him as a friend.

Peter Kowey, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, USA

When I returned to Philadelphia in 1981 to begin my first faculty job, Philadelphia was the centre of the electrophysiology (EP) world. Mark Josephson and Len Horowitz had established a vanguard clinical EP programme at Penn. They had begun an active surgery programme to map and remove foci of ventricular tachycardia, and were achieving good results in a high-risk patient population. I joined Toby Engel at the Medical Co

llege of Pennsylvania. We established a relationship with Michel Mirowski that led to the implantation of the third implantable defibrillator in the world at our site. While each of our centres pursued a different treatment paradigm for ventricular arrhythmia, we shared an interest in the mechanism by which drugs exerted their electrophysiological effects on tachycardia substrate.

The irony for all of us, of course, is that the implantable defibrillator developed so quickly and well that it eclipsed surgery and antiarrhythmic drugs to become the paramount therapy for patients with significant ventricular arrhythmia. Surgery was effective but associated with too many complications to make it practical for large numbers of patients. And drugs had too many limitations to make them reliable enough for sudden death protection, including proarrhythmia.

I do not believe that any of these developments could possibly have been anticipated when Mark and I began our careers in Philadelphia. But despite many fits and starts, it was Mark’s hard work, perseverance and genius that laid the groundwork upon which modern EP was built. The clinical application of concepts such as the excitable gap, resetting, and entrainment to name only a few, were made possible because of his early work in the EP lab and in the operating room.

Remembering what Mark did for our field is worthwhile for three reasons. First, Mark was a tireless worker and an advocate for clinical EP. He deserves our thanks for helping to establish our wonderful discipline. He correctly pointed out that EP procedures are no longer based on the precise knowledge of EP that was essential in the early days of our discipline, and that our fellows are poorly trained to understand important basic concepts.

Second, an appreciation of history is important to our fellows and young colleagues. I think of Mark and his generation as a bridge. It was Mark, Ken Rosen, Hein Wellens, Jay Mason, Jeremy Ruskin, Bernard Lown, and many others who took early theories in EP and applied them to the clinical setting. Theirs was a tremendous accomplishment and should not be taken for granted because without their contributions, our discipline would look much different than the sophisticated clinical science it is today.

And thirdly, and most importantly, literally thousands of patients would not have benefited from so many of the life saving therapies that all of Mark’s hard work made possible.

So thank you Mark. You will be missed.

David Steinhaus, medical director, Cardiac Rhythm and Heart Failure director, general manager, Heart Failure Medtronic and Julie Stephenson, Fellows Training and Transition, Cardiac Rhythm and Heart Failure Medtronic

One of Mark Josephson’s greatest passions was teaching cardiology and electrophysiology (EP) fellows. He considered it his mission in life to teach future EPs the critical skill of thoroughly understanding the 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) in order to diagnose arrhythmias and plan for appropriate treatment. Together with his closest friend, Hein Wellens, he developed what quickly became a quintessential educational course called “How to approach complex arrhythmias.”

This five-day, comprehensive course was most notable for the interactive learning approach developed by Mark and Hein. The professors would take turns asking for “volunteers” from among the participants. Brave fellows would come to the front of the room and stand before a huge 12-lead ECG projected onto the screen. Armed with a microphone and a giant pair of calipers, they would interpret the tracing guided by occasional questions and comments from the professors. Mark and Hein were very astute in assessing the individual knowledge of any volunteer and adjusted their guidance accordingly.

Mark and Hein established infamous rules of engagement for the course including:

- No ties allowed. If a fellow wore a tie to the programme, he ran the risk of having it cut off.

- When looking for a volunteer, it was best for the fellows not to look down… Any sign of weakness or uncertainty was a sure way of being “invited” to volunteer.

- Mark and Hein were always sensitive about giving everyone in the audience equal opportunity to volunteer and on occasion would call for a “gender change.

As anxiety-provoking as the course could be, all agreed it was an important rite of passage, opening their eyes to the many details contained in an ECG they had never noticed or understood before. Many years later, most electrophysiologists can vividly recall the tracing they interpreted.

The course thrived for 35 years with support from the Medtronic Education teams in Europe and the United States. An estimated 6,500 fellows across many generations and geographies were trained during that time. Understanding the timeless value of this course and the unique, effective teaching styles of Mark and Hein, footage from the course is being developed into an interactive e-learning experience that attempts to honour and share their legacy with many more generations of electrophysiologists to come.

Throughout Mark’s battle with cancer, he remained fiercely committed to the course, finding it especially therapeutic and energising. It was an honour to work with Mark and support him in the delivery of these courses. Ultimately, thousands of electrophysiologists are smarter and safer in their work because of Mark’s passion for teaching. He was a great friend to us all and will be greatly missed.