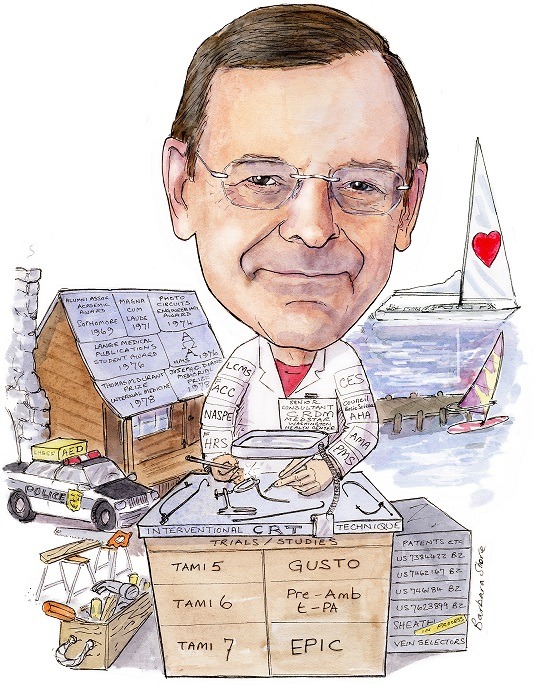

Seth J Worley (senior consultant, Cardiac Rhythm Device Management, MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC, USA) considers that cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) is one of the most important developments in the cardiac rhythm field. With the aim to enhance CRT outcomes, he pioneered the development of the “interventional CRT technique” with tools designed to facilitate and optimise left ventricular (LV) lead implantation. As founder of the Lancaster Heart and Stroke Foundation (LH&SF), Worley led the “Police AED Protocol”, a programme set out to empower the police force in Lancaster, USA, to prevent sudden cardiac death more effectively. He spoke to Cardiac Rhythm News in detail about these achievements.

When did you decide you wanted a career in medicine?

My father was a plastic surgeon who sometimes took me on weekend hospital rounds to meet his patients. On occasion he would show me before and after slides of burn and automobile accident victims whom he reconstructed. To better take care of patients, he invented devices to reduce the risk of nerve injury during complex facial reconstruction.

He was proud of being able to help people. He invented equipment to take better care of patients, not with an eye toward commercialisation. He inspired me.

Why did you choose to specialise in cardiology and electrophysiology (EP)?

Although surgically inclined during medical school, I consciously avoided a surgical career because I felt the demands of my father’s profession took a toll on our family. For me, cardiology represented the right combination of cerebral and surgical skills. Cardiology offers the opportunity to actively make a difference for patients. During my training, EP was just starting. Most of my fellow medical trainees were inexperienced with electronics and thus uncomfortable with pacemakers and the thought of EP. As a child I grew up working with my father in the basement on his medical inventions, building motors and radios. I grew up comfortable with electricity and electronic devices. For me EP was a natural fit. At the time, EP was also the most “surgical” of the areas within cardiology. The leaders in the field were no nonsense, dynamic and often outspoken, which somehow felt attractive. As a new discipline I felt there were opportunities for innovation.

Who are your career mentors and what have you learned from them?

My career mentors are somewhat atypical for an electrophysiologist. Richard Gentzler is an interventional cardiologist who, through example, taught me to always do what was needed to take the best care possible of the patient no matter how difficult or personally challenging.

He taught me to look at an unsuccessful procedure as an opportunity to learn, not as a failure. He also showed me that rather than giving up on a procedure sometimes one needs to improvise to do what is needed for the patient. George Klein is an electrophysiologist with whom I never worked directly. He is someone who worked outside the traditional EP “box”. Among other things, he used the transseptal approach to Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome ablation, a radical idea at the time that has been subsequently embraced by the EP community. In effect, he applied a traditionally interventional technique to EP. I am applying interventional techniques to improve device implantation. I am simply following his lead.

What is your biggest motivation for working in medicine?

I like to help people and make them happy, but then who does not? With interventional CRT, I have been able to make a difference in the lives of really sick people, many who had run out of options with other techniques and tools. With these tools and techniques I feel I am helping both patients and physicians.

In your view, what has been the most important development in EP during your career?

CRT and radiofrequency (RF) ablation. Both techniques, when properly applied, can make a dramatic and immediate improvement in patients’ lives. Both were disruptive innovations that were initially rejected by much of the EP community when introduced.

What are three important unanswered questions in cardiac rhythm management?

- How do I get the LV lead where it needs to go?

- How do I get the LV lead where it needs to go?

- How do I get the LV lead where it needs to go?

Most “experts” feel the venous anatomy markedly limits where the LV leads can be placed. While this may be true using traditional implant techniques, interventional CRT changes the paradigm. Like most disruptive innovations, interventional CRT requires change; something that is uncomfortable for many “experts” fixed in their ways.

Can you describe a memorable case you treated?

Last month I successfully implanted a transvenous LV lead in a patient who had two previously failed transvenous attempts and two sets of failed epicardial leads. She said it was like being risen from the dead. However, this example misses the point. Most patients with failed transvenous LV lead implantation using “traditional” techniques can be successfully implanted by anyone using the interventional tools and techniques I developed. It is not me. It is the tools and techniques.

You have been principal investigator of various clinical trials in cardiology and cardiac rhythm management; is there any trial in particular that you are most proud of?

I founded the Lancaster Heart and Stroke Foundation in 1989 to support clinical trials and provide community service (initially to teach cardiopulmonary resuscitation(CPR) and provide medications to those who could not afford them). Although I have been involved in many prestigious multicentre clinical trials over the years, I am most proud of our “Police AED Protocol” created and funded by the community service arm of the Lancaster Heart and Stroke Foundation. At the time we created the protocol, police were not allowed to use the automated external defibrillator (AED). The police seemed to be the ideal first responder, frequently on the scene of a cardiac arrest long before the ambulance. We created a protocol that was approved by the state department of health. We trained the police and provided the AEDs. We saved a lot of lives.

You have pioneered the application of interventional techniques and tools for device implantation; could you tell us about these inventions and how they have contributed to improve patient outcomes?

By comparison to the traditional approach, venoplasty of the obstructed subclavian vein reduces implant time, reduces the risk of implant failure and the need to abandon the existing leads and moving to the other side (increasing the abandoned lead burden). Most importantly, venoplasty reduces the need for extraction with its attendant risks. Although an essential skill for anyone who implants devices, most EP training programmes do not teach the technique despite being proven to be safe and effective. Subclavian venoplasty is a disruptive innovation that requires change, which many find threatening.

Using the tools I developed for the application of interventional techniques to LV lead implantation has the potential to reduce fluoroscopy time up to 50%, thus reducing radiation exposure to both the patient and the physician. Reduced fluoroscopy time translates to reduced procedure time. Longer procedures typically have a higher risk of infection. In addition, use of my tools and techniques can reduce the likelihood of an unsuccessful LV lead implantation from 8% to less than 2%. Successful LV lead implantation in a patient with chronic heart failure reduces mortality, improves quality of life and reduces hospitalisation. Physicians who use my tools and techniques can successfully implant patients who they were not able to implant previously using traditional tools. Interventional CRT is a disruptive innovation.

Another way to reduce implant time, improve LV lead placement and reduce the need for a surgical epicardial lead is by using another technique I have developed called the snare technique for LV lead implantation.

What are your current areas of research?

My current area of research is to compare the outcome of a CRT implant using the traditional vs. the interventional approach. We are looking at time to coronary sinus (CS) access, implant time, implant success and lead location. To this end I currently spend most of my time instructing physicians on interventional device implantation at their centre using the tools and techniques developed over the last 15 years. Providing instruction while the other physician does the procedure is a new experience for me. I initially developed the tools and techniques for use on my own patients. Interested physicians would come to my hospital where I gave presentations and performed live cases. Although some physicians were able to return and implement interventional CRT at their institutions, many had great difficulty pushing through the necessary change. My new approach, providing instruction while the other physician does the procedure, is a very different process. I am learning how best to teach others to use the tools and techniques at their centre. To this end I finally developed a simple portable model to teach CS cannulation using the interventional technique. I find that physicians who cannulate the CS on the model just before a case find it easy to cannulate CS using the interventional technique. In addition to in-person teaching, I am also an Advisory Board member for InterventionalCRT.com—an online learning platform that will give EP’s the opportunity to learn techniques to enhance patient care at their leisure.

You are the founder of the Lancaster Heart and Stroke Foundation (LH&SF); could you tell us what contributions have been made to the community through this Foundation?

The Lancaster Heart and Stroke Foundation (LH&SF) has helped the community in two basic ways:

- Supporting clinical trials in cardiology and stroke advances care in these areas by providing options for clinical trials without leaving the community. Participation in clinical trials has a “halo” effect of enhancing the quality of care outside of the clinical trials because physicians who participate become engaged in the latest advances as they follow the pathway to participation.

- Direct community service: CPR training was not conducted in the community. The Heart Foundation developed and supported a programme of CPR training in high schools. The Heart Foundation worked with drug companies to access and distribute medications to patients in the community who could not afford to purchase them on their own.

We developed an AED programme. Initially the LH&SF purchased standard defibrillators for the ambulances in the county that did not have them. With the advent of the AED, we saw an opportunity to treat sudden death more effectively by placing AED’s in the hands of police officers. Each police department in the county had its own command structure, and many were not initially interested. Over time, starting with the city police, we were able to involve all 37 of the police bureaus in the county. The city police became interested because the chief’s brother died suddenly. Each jurisdiction had a story that changed their attitude, frequently the sudden death of a member of the local community. The officers were eager to learn the technique. They clearly felt that it expanded their mission of community service.

Outside of medicine, what are your interests and hobbies?

Building things around the house and down at the dock, sailing and windsurfing. I love to improvise to fix things around the house like light switches, do a little plumbing and build shelves. I am the chief technical officer of the household. My family says they cannot manage without me!

Fact File

Current appointments

2017 Senior consultant, Cardiac Rhythm Device Management, MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington DC, USA

1982 Founder and president of the Board of Directors of the Lancaster Heart & Stroke Foundation

Recent past appointments

2005‒2016 Director of Interventional Implant Program Lancaster Heart Center, Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, USA

2000‒2005 Director of Electrophysiology, Lancaster General Heart Institute, Lancaster, USA

1995‒1999 Director of Electrophysiology and Pacing, Department of Medicine, Cardiology Division, St Joseph Hospital, Lancaster, USA

1996‒1997 Chief of Cardiology, St Joseph Hospital, Lancaster, USA

Education and training

1971 BA (Biology) CW Post College

1978 MD Temple University

1981 Residency in Internal Medicine, Strong Memorial Hospital

1984 Fellowship in Cardiology, Duke University Medical Center

Patents

Telescopic, separable introduce and method of using the same US 7,384,422 B2

Catheter sheath slitter and method of use US 7,462,167 B2

Introducer for accessing the coronary sinus of the heart US 7,462,184 B2

Catheter with flexible pre-shaped tip section US 7,623,899 B2

Professional memberships

1982 Cardiac Electrophysiology Society

1983 Council on Basic Science of the American Heart Association

1987 American Medical Association

1987 Pennsylvania Medical Society

1987 Lancaster County Medical Society

1989 Fellow American College of Cardiology

1990 North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology

2006 Fellow of the Heart Rhythm Society