“I believe, if you zoom out into the future, and you look back, and you ask the question, ‘What was Apple’s greatest contribution to mankind?’ it will be about health.” This was the vision set out by Tim Cook, CEO of the consumer electronics giant Apple, in an interview with CNBC in early 2019. Later that year, results from the Apple Heart Study demonstrated the potential use of a heart rate sensor on the Apple Watch to identify atrial fibrillation (AF)—the centrepiece of Apple’s aim to establish itself at the head of the market for consumer healthcare wearables.

“I believe, if you zoom out into the future, and you look back, and you ask the question, ‘What was Apple’s greatest contribution to mankind?’ it will be about health.” This was the vision set out by Tim Cook, CEO of the consumer electronics giant Apple, in an interview with CNBC in early 2019. Later that year, results from the Apple Heart Study demonstrated the potential use of a heart rate sensor on the Apple Watch to identify atrial fibrillation (AF)—the centrepiece of Apple’s aim to establish itself at the head of the market for consumer healthcare wearables.

Now, nearly two years on from Cook’s mission statement, the use of wearable tech has become more commonplace in healthcare settings, with arrhythmia management an area of particular focus. This is a space that sees household brands such as Apple, Samsung, and FitBit, whose devices are already widely in circulation, vying with medical device developers to bring wearable tech into clinical use. However questions still remain as to the scope and efficacy of consumer wearables in the management of cardiac arrhythmias. In this report, Cardiac Rhythm News explores some of the studies shaping understanding in this emerging field, and speaks to researchers leading the push.

To date, the Apple Heart Study has been the largest of its kind to garner insights on the use of a consumer wearable device, the Apple Watch, to identify episodes suggestive of AF. The study recruited almost 420,000 participants over eight months to demonstrate the yield and predictive value of the device in detecting AF. Participants were monitored for AF using an app that intermittently checked the heart-rate sensor in the watch for measurements of an irregular pulse. If detected, the wearer would receive a notification to schedule a telemedicine consultation with a doctor involved in the study.

Results of the study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in November 2019, demonstrated a low probability of participants receiving an irregular pulse notification and found that 34% of those who did receive a notification were diagnosed with AF. Whilst critics say the results suggest that the accuracy of the Apple Watch is still far short of more established AF monitoring techniques, others including principal author Mintu Turakhia (Stanford University School of Medicine, California, USA) suggest that the findings will “help patients and clinicians understand how devices like the Apple Watch can play a role in detecting conditions such as atrial fibrillation”.

Ongoing research

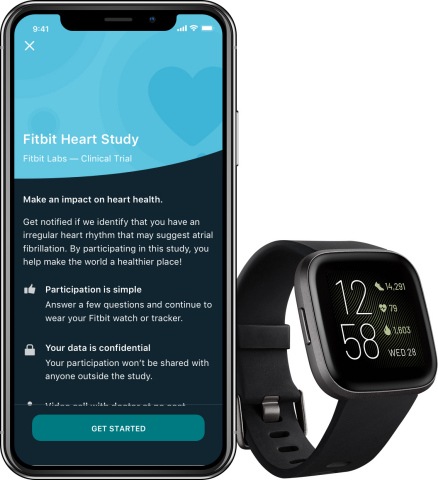

Apple is far from alone in recognising the commercial potential of using consumer wearable devices in the detection and management of arrhythmias, with devices and algorithms from Huawei—through the Huawei Heart Study—and Fitbit—which launched its own AF detection study in mid-2020, also looking to make inroads into the arrhythmia detection space, having received 510(k) clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and CE mark for its electrocardiogram (ECG) app to assess AF in September 2020.

Steven A Lubitz, cardiac electrophysiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA is the principal investigator in the Fitbit study. Lubitz sees the large number of consumer wearable devices already in circulation as an advantage in the study. “We can easily and rapidly recruit large numbers of participants simply by inviting existing consumers to participate. It would take a very long time to accrue and enrol such numbers using conventional recruitment approaches,” he said. “We’re able to rapidly power our study to determine quickly whether the alerts that the algorithm generates are accurate or not.”

A key question linked to the proliferation of consumer-grade wearables in healthcare is the accuracy of readings from the devices, and data is still emerging. In a study published in the journal Heart Rhythm in May 2020, Nicholas Sequeira (University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada) and colleagues sought to examine the accuracy of four common wearable devices—Apple Watch, Fitbit Charge HR, Garmin VivoSmart HR, and Polar A360—in measuring heart rate during paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

The study team gathered data from 52 patients by placing one device on each wrist during an electrophysiological study at which SVT was induced. The device-measured heart rate was obtained by using the highest heart rate measured by the device during each SVT episode, and this was compared with measurements from a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), for which the rate during the last five seconds of SVT was averaged. The study team concluded that all of the wearable devices were inaccurate for short-duration SVT, while only some of them provided accuracy in measuring longer duration SVT.

Important frontier

In August 2020 European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and other international bodies acknowledged that that there exist “clear concerns” over the accuracy of wearable technologies, but insisted that they represent an “important frontier in health evaluation, with the potential to provide readily accessible health data for large segments of the population, including those not captured by conventional monitoring techniques.”

According to Nassir Marrouche, professor in cardiovascular medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans, USA, and chair of the Heart Rhythm Society’s digital health committee, the question of the adoption of consumer wearables in the detection of arrhythmias is neither ‘if’ nor ‘when’. “Digital medicine is the new medicine,” he told Cardiac Rhythm News, discussing the potential uses of wearable tech in the field. “Our patients are expecting us to read the watch on their wrist,” he commented, adding, “the challenge we are facing is how to integrate this into our daily practice.”

A patient sending an ECG tracing, captured by their wearable device is nothing new, Marrouche says, and indeed as practitioners and patients have become increasingly attuned to the need for remote consultation, sped up by the COVID-19 pandemic, this is only likely to continue. However this itself is a new challenge for cardiologists.

“Consumers are coming to us now saying I have caught the new symptom on the block. I have my Fitbit, or my Apple Watch or my Samsung Active showing me my heart rate is 170 when I am sitting.” He notes that it is the role of the physician to interpret the data and educate the patient to understand the masses of data that they now have access to. While this is a new challenge, Marrouche believes that this is also where the greatest opportunity lies. “The breakthrough will be, in ten years from now or less, when we start seeing more and more prevention. The more tools we give people the better we will get,” he comments.

David Slotwiner (New York-Presbyterian Queens and Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, USA) has been among the other leading voices from within the electrophysiology community to predict the advance of wearable tech in the management of arrhythmias.

“I think we are witnessing an important inflection point in how care will be delivered going forward with significantly more data captured by patients outside of the traditional boundaries of the medical establishment,” Slotwiner told Cardiac Rhyhtm News. Wearable devices will allow more immediate access to data that would otherwise not have been possible, Slotwiner says, but he points out that while the technology is developing rapidly, the frameworks to incorporate these devices into existing healthcare systems are less straightforward.

Labour intensive

“Many consumer products are not used to functioning in the medical environment,” he comments. “The simple act of having a patient send me their Apple Watch ECG tracing requires me to break rules. They do not like us to use email for patient communication, but our portal at the moment does not accept attachments. The only way to get that attachment into the electronic health record is for me to import it or to ask my staff to import it, so it is very labour intensive.”

Slotwiner sees physician reimbursement as another area of challenge, acknowledging that this has yet to be fully understood by practitioners and healthcare providers. “Reimbursement really drives practice and to drive practice to these more ongoing interactions to digital health tools we are going to have to continue to evolve the payment structure to allow that,” he says.

Despite these challenges, Slotwiner believes that the march towards wider use of wearables in healthcare is inevitable. “There is an enormous amount of fear amongst my colleagues and the medical establishment of change, and giving patients this power, which I totally disagree with,” he comments. “My strong belief is that it will end in better care with patients more engaged and so we just have to invest the time and resources to figure it out.”

Apple’s second major study of AF detection and prevention, Heartline, is already underway, and alongside the Fitbit heart looks set to the major studies shaping understanding of the role of consumer wearables in arrhythmia detection in the years ahead.

Should medical device manufacturers be concerned about the rising tide of consumer wearables in healthcare settings? Slotwiner believes so. “I think they should be worried!” he exclaims. “It is only a matter of time until these wearables get more sohpisticated and can record more data so I do not think anyone should get too content that they are invulnerable to change.”