Wireless or leadless pacemakers, commonly implanted in adults, may be a safe and effective short-term option for children with slow heartbeats, according to new research published today in Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Heart Association.

Wireless or leadless pacemakers, commonly implanted in adults, may be a safe and effective short-term option for children with slow heartbeats, according to new research published today in Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Heart Association.

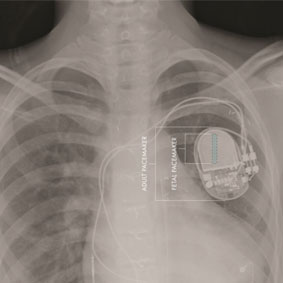

Children with a heartbeat that is too slow (bradycardia) require pacemakers—devices surgically implanted under the skin of the chest that transmit electrical impulses to regulate the heartbeat. Standard pacemakers use tiny wires, or leads, that are connected to the heart to deliver the lifesaving pacing (electrical signals to keep the heart beating normally). Active, growing children, however, are at higher risk for wire fractures and pacemaker complications because the wires in typical pacemakers may break or malfunction, according to researchers.

The leadless pacemaker is a miniature device, the size of a AAA battery, and it is self-contained and placed directly inside the patient’s heart. It does not require tiny wires (leads) to help regulate the heartbeat. This study provides the first data on leadless pacemakers in a paediatric population in a real-world setting.

“The leadless pacemaker works very well in children, just like it does in adults. We found it may be safely implanted in select paediatric patients that need pacing,” said lead study author Maully J Shah, director of cardiac electrophysiology in the Cardiac Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a professor of paediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, both in Philadelphia. “Our study’s results indicate select children may be considered candidates since they may benefit greatly from leadless pacing. However, because of the current technology, which uses a very large catheter designed for adults to place the leadless pacemaker and lack of reliable future extractability of the pacemaker, the wider paediatric population is not able to benefit from this device.”

The Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) maintains a registry of pacemaker implantations performed at 15 centres across the US, UK and Italy. During the study period (2016–2021), cardiac electrophysiologists implanted the leadless device in carefully selected patients who were experiencing a slow heartbeat. Researchers evaluated data in the registry for one brand of leadless pacemakers to analyse how well the leadless pacemaker performed in 63 children, ages four to 21 years (average age 15). For 77% of these children, this was their first pacemaker.

The analysis found:

- 62 of the 63 children had the leadless pacemaker successfully implanted, and the heart’s electrical parameters were stable within the first 24 hours.

- During an average follow-up period of about 10 months, the pacemaker was effective in its overall performance, including battery longevity, low pacing threshold (signals if pacemaker is performing well) and ability to detect the heart’s native electrical beats. Pacemaker batteries typically last 5–10 years, depending on how often the device is needed to maintain regular pacing, added Shah.

- Overall, 16% (10) of the children experienced complications after receiving the leadless pacemaker. Most of these were due to minor bleeding, which was treated promptly and easily. There were three major complications—one blood clot in the femoral vein of one patient; one cardiac perforation; and one patient had sub optimal pacemaker function requiring removal of the pacemaker after one month.

“Using adult catheter-guided delivery systems in children is challenging and may increase the risk of major complications. Since these are big catheters, selection of patients by size is very important. Two out of the three complications occurred in patients weighing less than 60 pounds,” Shah said. “The femoral vein in the groin is the conventional route to place the leadless pacemaker. For some patients, especially the younger and smaller children, the jugular vein (in the neck) was a better option because it provides a more direct route to implant the tiny pacemaker in a smaller heart.”

During the follow-up period after implantation, the leadless pacemakers continued to have stable performance, and there were no reported complications. The researchers have now converted this retrospective study to a prospective study and plan to follow these patients for an additional five years.

“Leadless pacemaker technology is the wave of the future,” Shah said. “This is an excellent technology that may be offered to a wider paediatric population. However, techniques and tools to place the device must be designed for smaller patients, specifically children, and there needs to be a mechanism to remove and replace this pacemaker without surgery when the battery runs out since paediatric patients will likely require pacing for the rest of their lives, which is several decades after implantation.”

The major limitations of this study are the small study size and short term follow up.

“This initial report looking at implanting leadless pacemakers in children and adolescents may provide information to guide clinicians on how to select children who might benefit from a leadless pacemaker,” said Kenneth A Ellenbogen, co-author of the 2018 the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) and Heart Rhythm Association (HRS) Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay, and Harold W Kimmerling, Professor of Cardiology at the VCU School of Medicine in Richmond, Virginia. “This new information may also allow more access to leadless pacing for children.”